Doctors for a sustainable future

Doctors are a key part of the medical community and should lead the decarbonisation of healthcare and advocate for sustainability, according to Dr Jesse Gale, chair of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmology’s (RANZCO’s) sustainability committee. Sharing this view online at RANZCO’s 52nd scientific congress earlier this year, Dr Gale said climate change is both an existential and public health threat and actions should focus on reducing the burden of human activity on the environment. “Dealing with climate change will also deal with several other environmental concerns and should have co-benefits for equity and public health, which are concerns that doctors should be advocating for.”

Dr Gale shared results from an online survey of RANZCO fellows which showed concern for climate change is higher in the general population in Australia and New Zealand than among ophthalmologists, but 68% of fellows agreed climate change due to human activities is an urgent issue. Other findings revealed female and younger ophthalmologists support climate action and advocacy more, while rural ophthalmologists are most opposed. Of the respondents, 57% thought RANZCO should advocate for climate change mitigation and adaptation, while 68% agreed public hospitals should have sustainability as a key performance indicator. “When it comes to decarbonising our hospitals and practices, the biggest contributors are energy and transport, including staff commutes, patient visits and supply deliveries,” said Dr Gale. “Reducing transport emissions in ophthalmology will mean delivering care closer to home (and) closer to public transport hubs, and reducing unnecessary visits and low-value care visits.”

Dr Jesse Gale

Measuring emissions

Looking at cataract surgery in New Zealand, most emissions come from procurement, since New Zealand’s electricity is largely from renewable sources and transport represents a smaller fraction (about 15%) than elsewhere. Clinics can use the Eyefficiency app to gain a deeper understanding of where their inefficiencies lie to achieve better surgical sustainability, said Dr Gale. The software is quite simple and can generally be used as a stopwatch to measure the amount of time spent before, during and after surgery, to improve workflow and systems for efficiency in the operating theatre, he explained. There are also more complicated calculations, such as measuring greenhouse gas emission sources, hospital floor areas allocated to cataract surgery, operating room energy consumption and waste disposal emissions, based on the weight of the rubbish bag and the distance to the landfill, he said, though these may require a more dedicated and experienced researcher.

Measuring the carbon footprint of the Kāpiti clinic where he works, Dr Gale found single-use supplies and excessive packaging were its greatest emission source. “To cut emissions, we need to reduce consumption and reuse and recycle as much as possible, including gowns, drapes and perhaps even blades. Although this work requires co-operation within the industry, there are things we can change immediately.”

Environmental cost = health cost

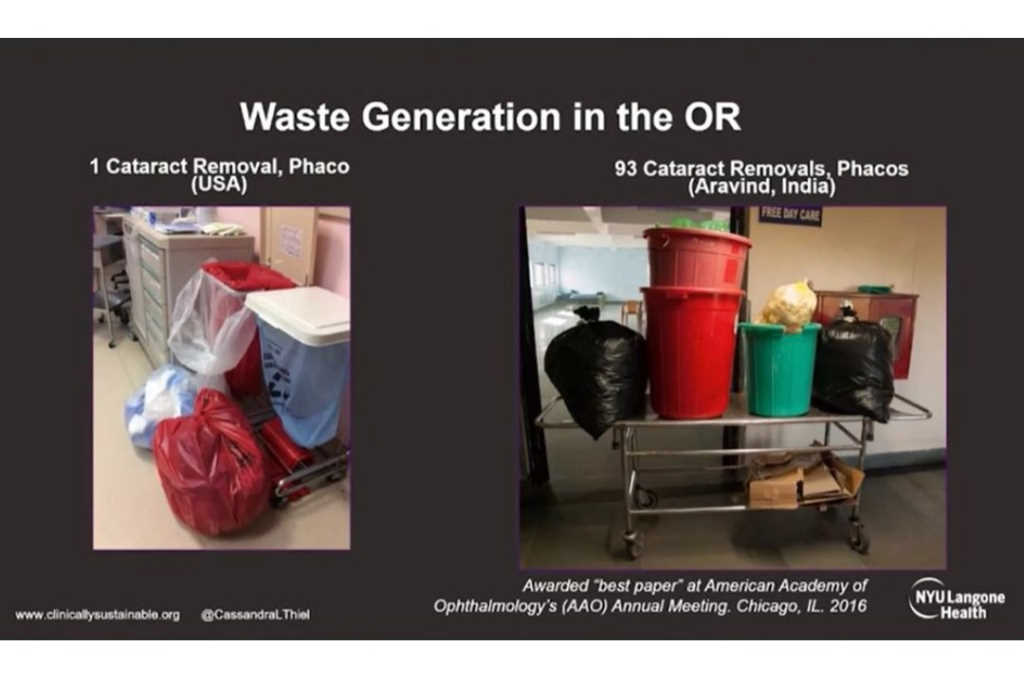

Repeating and extending her talk from last year’s RANZCO NZ Branch conference, RANZCO 2021/2022 Congress guest speaker Dr Cassandra Thiel, associate professor at New York University Langone Health, said ultimately the cost of pharmaceutical waste is a financial issue as it impedes access for patients. Globally, healthcare is estimated to be responsible for approximately 5% of greenhouse gas emissions. In the US this sits at 10% of the country’s total emissions, while in Australia it’s at 7%, said A/Prof Thiel. “A single phacoemulsification emits about 180kg CO2 equivalents, which is about one week of living for the average British person. Over 50% of these emissions originate from the procurement of supplies, which are mostly single use. Our financial and environmental resources are finite. In healthcare, we have often been given a pass on both of these but in the end, we cannot afford – financially, environmentally or socially – to keep doing what we are doing.”

A/Prof Cassandra Thiel

A way forward could be to adopt the practices of low-resource and high-volume settings like the Aravind Eyecare Centre in India, which is structured and resourced to generate far less waste, she said. “The carbon emissions at Aravind are about 5% of what they are in the UK. Given how well this functions, it’s a really great model to replicate; very cost effective and environmentally effective, while infection rates and other (negative) outcomes are lower compared to the US.”

RANZCO has released preferred-practice guidelines* covering some easy options for cataract surgeons to try immediately, while others will be expanded over time, said Dr Gale. Currently these include stopping postoperative antibiotic drops in routine cases that use intracameral antibiotics; using smaller drapes; avoiding the use of medical gases such as high-flow oxygen under the drape; and considering topical anaesthetic routinely as it reduces consumption compared to injected anaesthetics.