Trusting tech and your instincts

A few months ago I was supervising a 5th year optometry student’s primary care clinic. It was a simple dry eye follow up. The patient Josh (not his real name) was a 26-year-old male economics student, who one could say erred on the side of being a pedantic hypochondriac. Nevertheless, the persisting ‘glare’ and ’ghosting’ in his left eye, even after managing his nocturnal lagophthalmos and uncorrected astigmatism, piqued my interest.

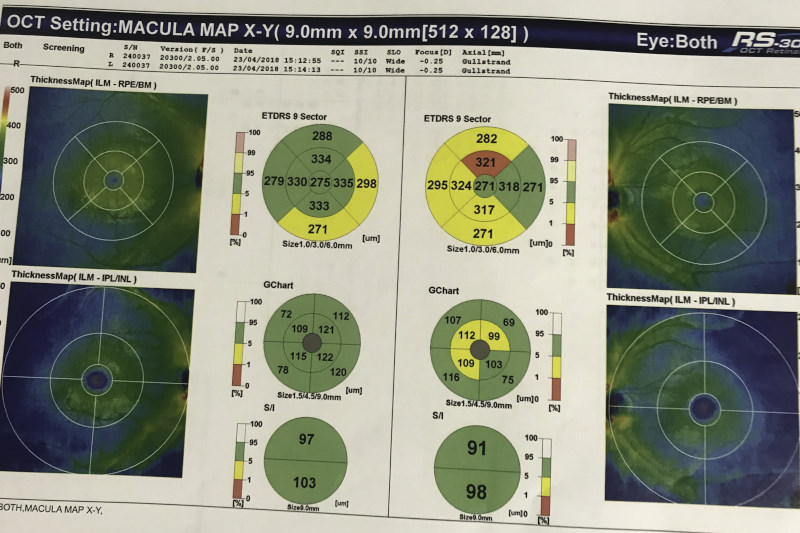

After doing a red cap test and noting the desaturation in the left eye, I directed the 5th year student to do macular OCT scans on both eyes, with the results showing retinal nerve fibre layer thinning, as well as the ganglion cell thinning in the ganglion cell analysis (GCA) for the left eye. Family history, pupils and optic nerve head appearance were all unremarkable, but based on the OCT findings I sent him to his GP to get an MRI scan and neurological work-up as I had recently written an article on multiple sclerosis (MS) and the eye.

MS is a progressive disease that most commonly affects the brain, spinal cord and optic nerves, where sclerosis of axons occurs consequent to demyelination or independently from it. We all know optic neuritis is the most common first sign of MS - present in 20% of diagnoses - but I had recently learnt that greater than 50% of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) bodies (which are essentially unmyelinated axons) are located in the macula, and by comparing overall macular thickness to ganglion cell layer (GCL) analysis, we are able to directly measure the loss of axons from MS without extraneous variables such as loss of myelin mass.

The GP disregarded my findings and informed Josh the MRI was not indicated and so he would have to pay A$550 for the scan. Fuelled by my confidence from the optometric literature I had read, I found him a new GP who agreed with me and wrote the referral for the MRI scan (which eventually was covered by Medicare). During this time, I had attended another CPD lecture series on neuro-optometry and was writing a further review. One of the lecturers, American optometrist Dr Kelly Malloy, had stressed the importance of us as optometrists of familiarising ourselves with MRI and CT scans and knowing the indications and contraindications of different scans. This is because of the high level of trust our patients have in us, due to the amount of contact time we have with them compared to other health professionals and our gateway role in the diagnostic process, she said, using an example from her practice where she had reviewed a patient’s films and helped find a misdiagnosed ICA aneurysm.

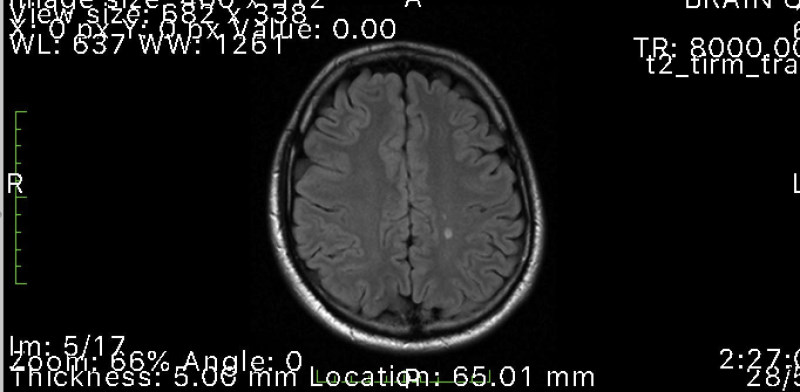

Ironically, the day after writing my neuro-optometry review, Josh sent me his MRI scans. He appeared to have a couple of demyelinating lesions typical of MS, which were confirmed by both the GP and his neurologist. The neurologist then arranged for a lumbar puncture and confirmed the diagnosis of MS, prescribing Josh oral tecfidera capsules, which thankfully for Josh were also covered by Medicare. All this took place before Josh manifested any signs of MS so he is very grateful.

Fig 2. MRI scan showing demyelinating lesions typical of MS

This case shows how important our role as clinicians is and how we can impact the outcome for a patient as long as we keep our eyes open, perform the indicated tests well and have confidence in our findings. Although clinical optometry, especially in neurology, is a new frontier and we may experience hurdles in asserting the validity of our opinions (as I did with the first GP), it is well worth pursuing as we can impact our patients’ quality of life profoundly.

Australia-based optometrist Layal Naji is a junior visiting research fellow and clinical supervisor at the University of New South Wales.