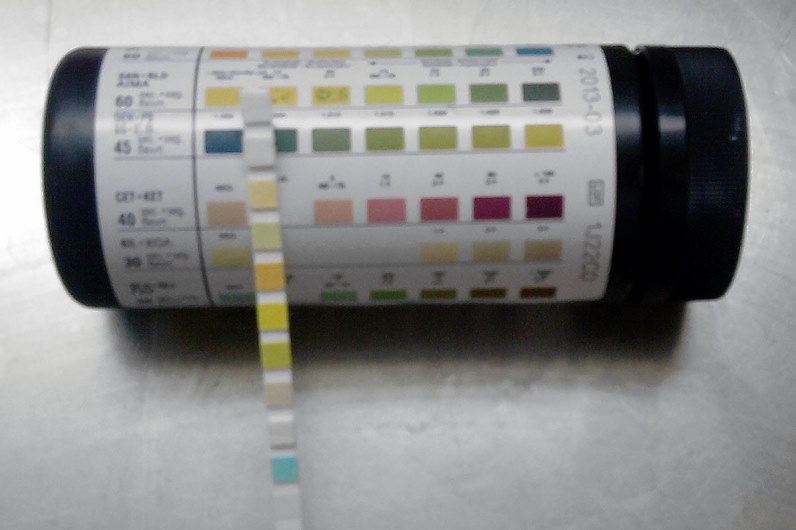

Urine test for river blindness

Scientists at Scripps Research have developed a urine dipstick test to detect the parasitic worms that cause river blindness (onchocerciasis), a tropical disease that afflicts 18 to 120 million people worldwide.

The new, non-invasive test may provide an inexpensive method of determining in real time whether a person has an infection, which would give public health officials and doctors critical information for tracking outbreaks and treating current infections.

“River blindness affects individuals both in Africa and Latin America, and because many of these endemic regions are difficult to access, what is needed in the field is an inexpensive point-of-care means to monitor the disease,” says Scaggs Institute for Chemical Biology professor at Scripps Research, Kim Janda.

River blindness occurs when the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus takes up residence in the skin. Adult worms pump out babies (microfilaria), which are ultimately re-spread by blackfly bites. The microfilariae can migrate to the eye and die, releasing toxins and causing inflammation. People with the disease will slowly go blind without medical intervention.

Janda says onchocerciasis monitoring and evaluation are especially necessary steps for people leading elimination efforts. To know if these efforts are working, doctors need to be able to show when disease transmission has been interrupted..

Currently, onchocerciasis elimination programmes rely primarily on mass drug administration to suppress and eventually eliminate transmission of Onchocerca volvulus. Without a means to evaluate if an infection is ongoing, however, it’s hard to assess if prevention efforts are working—and if it’s safe for people to stop taking medication.

The new test took over 10 years to develop, but it is now ready for manufacturing and testing in the field, the researchers said. It is based on designer antibodies the researchers made which create a unique biomarker that only shows up when a human host has metabolised a worm neurotransmitter called tyramine. Humans then secrete this biomarker in urine, and it can be detected with the dipstick.

Janda said this inexpensive, non-invasive test is the first to use a metabolite produced by adult worms, and that the dipstick could ultimately help to address critical gaps in the surveillance and treatment of river blindness.