Orbits in orbit: the weightless eye

Outer space may be filled with wondrous mysteries and the promise of discovery, but a forgiving environment for the human eye it is not.

As with many parts of the body, the very structure of the eye is challenged by weightlessness. As spaceflight becomes a commercial enterprise – with Sir Richard Branson having briefly left the planet with Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin launching 90-year-old Captain Kirk actor William Shatner into space in 2021 – more insight on the visual system during long-term weightless (zero-g) ventures is vital.

Orbits in orbit

One of the largest breakthroughs in understanding the effects of microgravity and the eyes came from the Twins Study performed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) Human Research Programme in 2015. The experiment involved sending now-retired astronaut Scott Kelly to the International Space Station (ISS) for a year while his twin brother, Mark Kelly, remained on Earth as the control.

Astronaut twins Mark (left) and Scott Kelly

Larry Haug, retired data systems supervisor for the Apollo programme and ground data systems mission manager for the Hubble Space Telescope, said the study demonstrated dangerous effects on the human body, including vision impairment due to insufficient circulation of oxygen in ocular tissues. “In microgravity, the muscles that hold the eyes together deteriorate, resulting in reduced vision, particularly depth perception,” Haug explained. “Scott’s physiological changes consisted of bone and muscle loss. I frequently heard about astronauts growing ill after their first day aboard the ISS due to the way weightlessness affects the inner ears. Space sickness and eye health in zero-g are still challenges NASA and other space agencies will need to address for future expeditions into deep space, such as missions to Mars.”

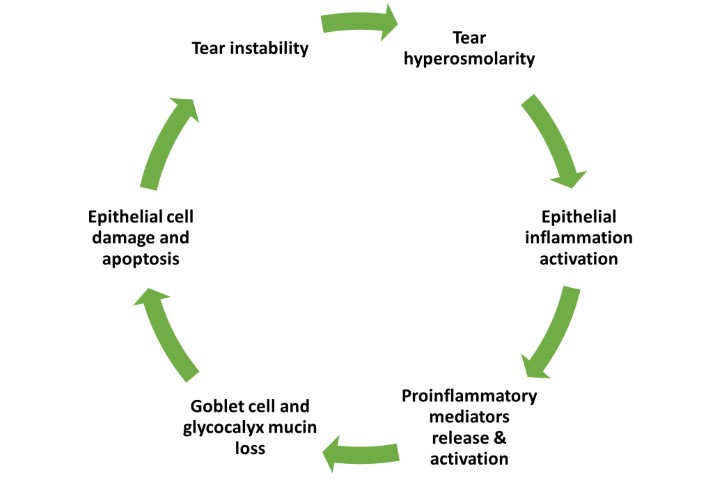

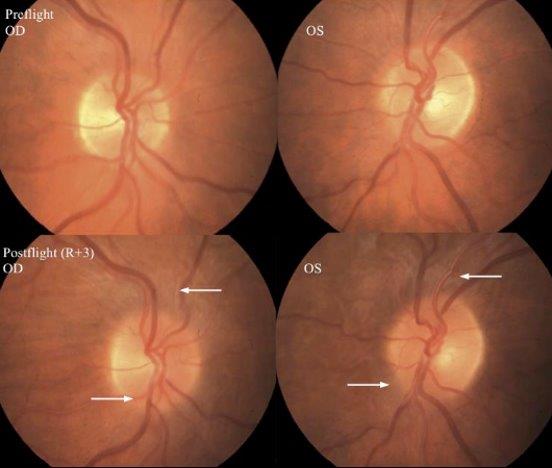

Space-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), is a group of complications the human eye experiences after prolonged weightlessness. According to NASA researchers, symptoms from reduced hydrostatic pressure in the brain include headaches, visual scotomas and drastic hyperopic shifts of up to 1.5 diopters, nerve haemorrhaging and swelling, plus retinal irregularities such as choroidal folds and optic disc oedema (Fig 1). Some of these conditions present as early as three weeks after beginning spaceflight.

Fig 1. Pre-flight and post-flight funduscopic images from an astronaut after a six-month mission. Post-flight images reveal optic disc oedema and choroidal folds (arrows). Credit: NASA Risk of SANS Evidence Report

Cosmic complications

Clinical development manager for Heidelberg Engineering, Steve Thomas, warned astronauts’ eyes were especially susceptible to anatomical changes which led to extensive testing being conducted throughout each astronaut’s six-month stay in orbit. “The use of optical coherence tomography (OCT) aboard the ISS was designed to look at the ways the eyes interact with changes in the brain,” said Thomas. “Before crew members go up, they’re imaged by a variety of eye devices to create baselines. Then, during their mission, they’re scanned multiple times at regular intervals. We’ve learned from the data that gravity is an essential part of our healthy existence on Earth, and it can be quite a problem when it’s not there.”

One of the benefits of observing the ocular system in space is a better understanding of the relationship between cerebrospinal fluid and intraocular pressure (IOP), said Thomas. Recent studies have even suggested prolonged microgravity exposure increases subfoveal choroid thickness and may contribute to SANS symptoms experienced by astronauts.

European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst, Expedition 40 flight engineer, performs an eye exam for the Ocular Health experiment. Credit: NASA

“Fluid pressure from every human heartbeat is more uniformly distributed throughout the body when surface gravity isn’t there to normalise it,” explained Thomas. “That means the head, being closer to the heart, receives more fluid than necessary. This is thought to be a potential mechanism for SANS and elevated intraocular pressure, leading to conditions such as glaucoma.”

Gravitational gradients

Back on Earth, a study published in September 2021 discovered Schlemm’s canal collapses after patients are exposed to microgravity simulations via 15 minutes of 20-degree head-down tilt (HDT) positions. Insufficient aqueous humor drainage then elevates IOP, increasing the risk of glaucomatous damage.

Dr Katie Baston, an ophthalmologist at the Harman Eye Center in Virginia, US, explained that intracranial pressure is another concern in a microgravity environment. “When cerebrospinal fluid no longer has the gravitational pull we’re used to on Earth, it presses on the optic nerve from behind, creating pressure from outside the eyeball. This produces a condition similar to idiopathic intercranial hypertension, which is still a major issue to address for long-term spaceflight.”

Astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor examines her eye with a fundoscope aboard the International Space Station with remote support from doctors on the ground. Credit: NASA.

Scientists agree zero-g and its equally hazardous companion, radiation, both pose enormous obstacles for sustaining humanity away from Earth. Our planet truly provides a unique environment to support human life, said Thomas. “As soon as you move away from Earth, a whole host of problems begin materialising for normal bodily functions. There’s a lot of work going on by really bright people to either mitigate or solve these health risks, and I believe we’ll find a way.”

When observing how the human eye – and indeed, the entire body – depends on its physical environment for proper function, Dr Baston said Earth acts as the perfect host for even the most routine of daily activities. “The more research we do and the more we learn about the human body, the more we realise the amazing complexity of our physiological processes. It’s absolutely mind-blowing to think how adapted our bodies are for exactly the planet we live on. But since we figured out how to live inside submarines, we can surely figure out how to maintain healthy eyes in space.”

Jakob Sauppe is a freelance healthcare and technology writer based in Virginia, US.