Update on herpes zoster ophthalmicus

This update will answer some of the common questions surrounding herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) and highlight recent research, including several key findings from studies performed in Auckland.

What is herpes zoster?

Herpes zoster (HZ), also known as shingles, is usually characterised by pain, followed by the development of a vesicular rash, which is unilateral and typically affects one dermatome. Without vaccination, up to one-third of people are estimated to be affected by shingles during their lifetime, rising to one-half of those who live to 80 years.

Shingles is caused by reactivation of the varicella zoster virus, with the initial infection occurring as varicella (chicken pox). The virus remains dormant in cranial nerve and dorsal root ganglia until it reactivates due to waning cell-mediated immunity that occurs with advancing age. The most common location of herpes zoster is the torso.

How often does HZO affect the eye?

The second most common location of HZ is the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, termed HZO; it represents approximately 10-20% of HZ cases. HZO involves the eye in over 50% of cases.

What are the manifestations of HZO?

HZO can cause inflammation throughout the eye, including conjunctivitis, keratitis, iritis/uveitis, episcleritis/scleritis, retinal perivasculitis and necrosis, and optic neuritis.

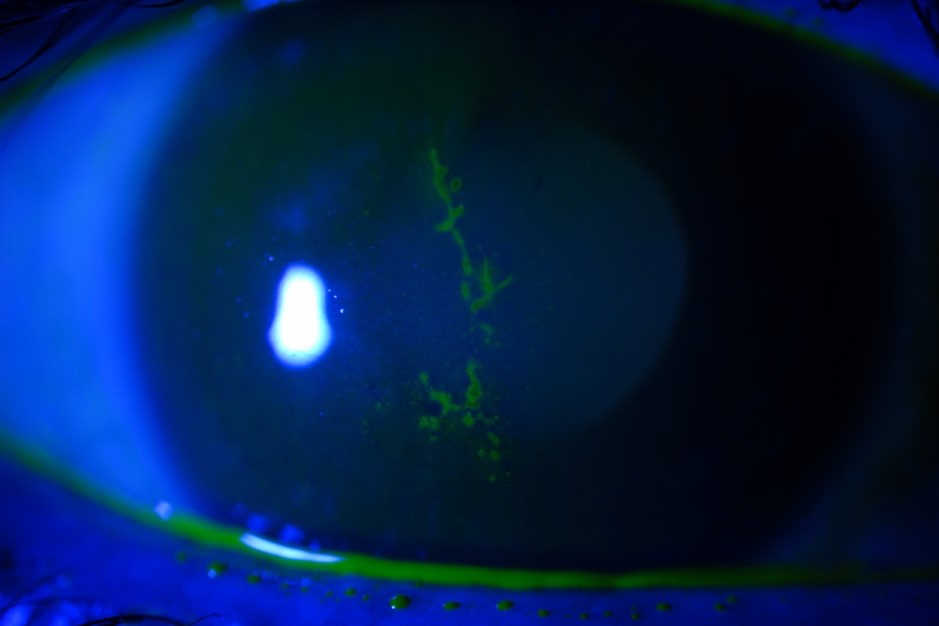

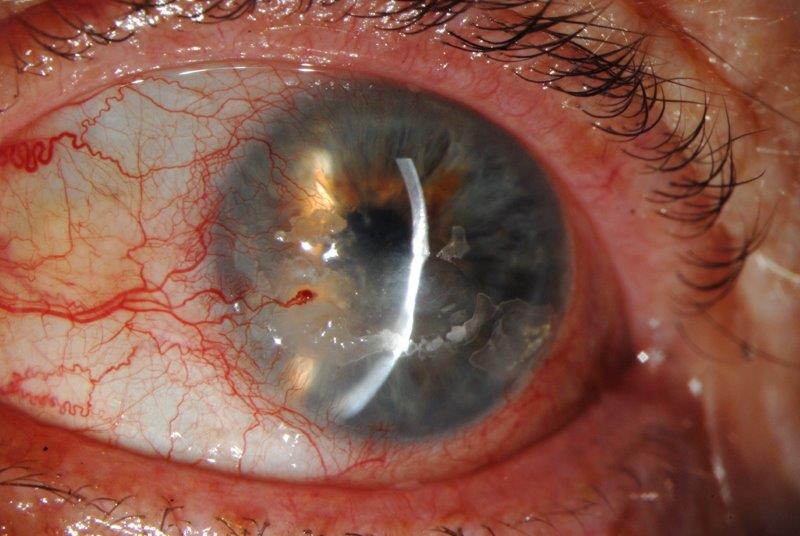

Corneal involvement occurs in up to two-thirds of patients with ocular findings in acute HZO1. Corneal manifestations are also varied and can include epithelial keratitis (Fig 1), stromal keratitis, and endotheliitis.

What are the complications of HZO?

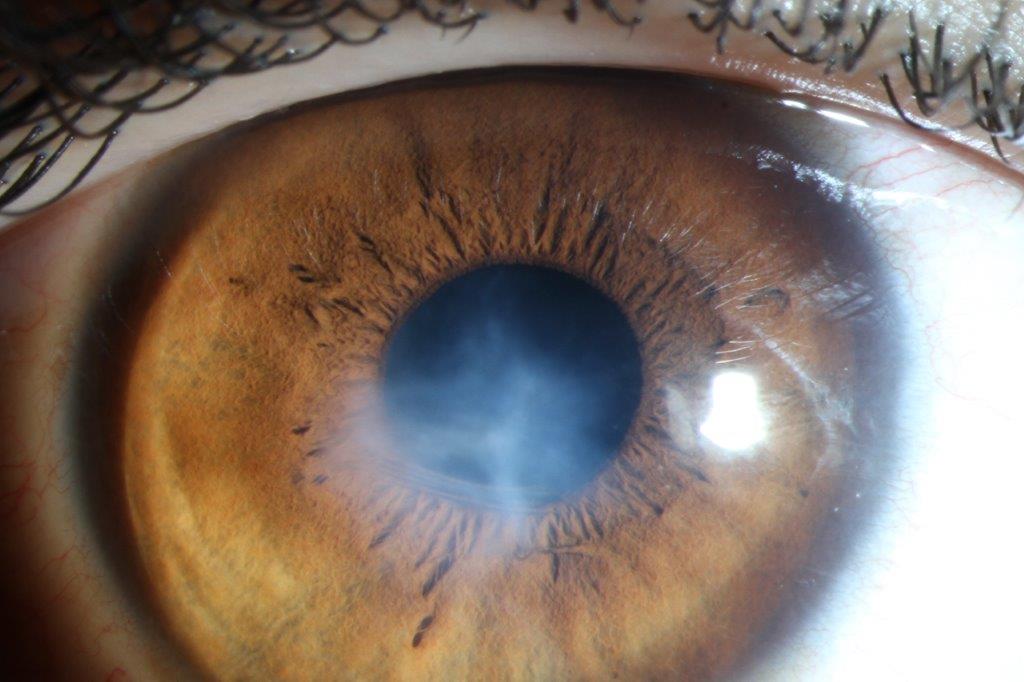

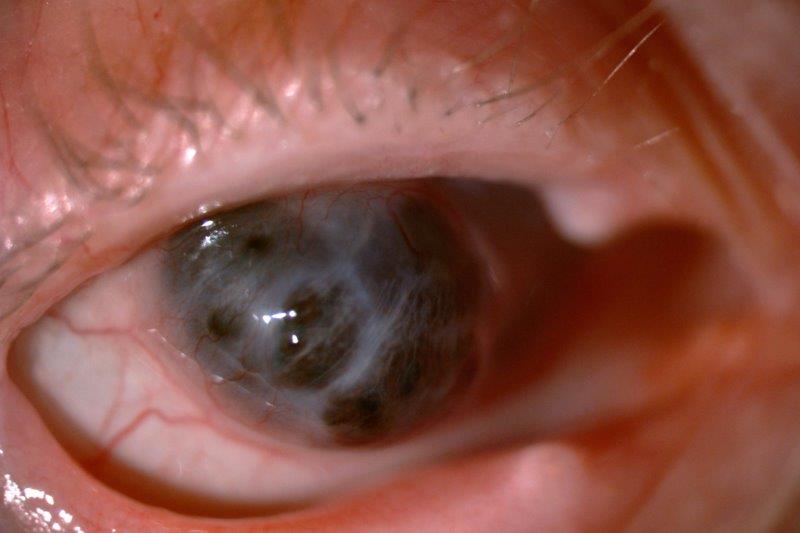

HZO can result in permanent loss of vision, persistent pain and decreased quality of life. Chronic complications of HZO with ocular involvement include recurrent keratitis or uveitis, corneal scarring, lipid keratopathy, neurotrophic keratopathy, band keratopathy (Fig 2), cataract, glaucoma and, rarely, corneal melt and/or perforation (Fig 3).

Fig 2. Band keratopathy and corneal thinning

Fig 3. Severe corneal melt and perforation

Neurological sequelae of HZO may include post-herpetic neuralgia (pain or itch that occurs beyond three months after rash onset), cranial nerve palsies and optic neuritis. Post-herpetic neuralgia is the most common complication and occurs in approximately one-third of patients aged 65 or older. There is an increased risk of cerebrovascular accident (stroke) following HZ, with the highest risk in the year following HZ, and a greater risk following HZO, compared to HZ of other locations2.

How often does HZO cause vision loss?

The loss of vision due to HZO can be immediate or delayed, with over 20% of patients developing a chronic course that can result in further complications and loss of vision over time3. In a recent study of 869 patients with acute HZO seen in Auckland over a decade, approximately 1 in 10 individuals developed moderate visual loss (best corrected acuity ≤20/50) while 1 in 30 individuals had severe visual loss (best corrected acuity ≤20/200) attributable to HZO4. Factors associated with vision loss included older age, uveitis, Caucasian ethnicity, and immunosuppression.

When should HZO patients be examined by an ophthalmologist?

Patients with acute HZO are often referred to an eyecare specialist at the time of diagnosis for an evaluation to determine whether ocular involvement is present, particularly those with ocular symptoms. Ocular involvement most frequently develops within the first two weeks following the onset of rash. For patients seen within the first week of rash onset and without ocular involvement, providers should be aware that involvement could still develop, particularly iritis. As a result, patients should be advised to return if ocular symptoms develop, or a second exam could be scheduled 1-2 weeks later.

How is HZ treated?

Acute HZ is treated with antiviral medication, typically with oral acyclovir (800mg five times daily) or valacyclovir (1,000mg three times daily) for seven days (or 10 days if immunocompromised). For patients who have systemic symptoms (pneumonia, encephalitis, hepatitis), a rash affecting multiple dermatomes, or are severely immunocompromised, hospitalisation for intravenous treatment should be considered.

Antiviral medications are likely to be most effective if given within 72 hours of rash onset but may be considered up to seven days after rash onset. In the past, oral corticosteroids were sometimes prescribed along with antiviral medications, although this practice is now controversial.

The treatment of ocular manifestations, such as various forms of keratitis, is beyond the scope of this update. However, it is worth noting that recent evidence suggests topical antiviral medication may be effective in treating pseudodendrites associated with HZO5.

Do prophylactic antivirals reduce the risk of HZO complications?

Acute treatment of HZ with antivirals initiated promptly (within 72 hours) following rash onset has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of some sequelae, such as acute and chronic pain and ocular complications6,7. According to a recent retrospective study conducted in Auckland, there may also be a reduced risk of stroke when antiviral treatment is initiated within 72 hours8.

It is currently unknown whether there is any benefit to longer-term antiviral treatment after the initial acute HZO. This is currently being studied in the ZEDS (Zoster Eye Disease Study), a multi-centre (USA, Canada, NZ) double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial to determine whether valacyclovir treatment (1,000mg/day) for one year following HZO reduces the risk of chronic complications in immunocompetent adults. Eligible patients must be 18 years old or older, have had HZO keratitis or iritis and be enrolled within six months of the rash onset. We have established a study site in Auckland and are actively recruiting. To refer a patient, please contact the study coordinator, Robyn Cochrane, at robyn.cochrane@auckland.ac.nz

Is a vaccine available for shingles in NZ?

This year, a recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) became registered in NZ for the prevention of zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia for those over 50 years and for adults aged 18 or older at increased risk. A two-dose primary course (doses given six months apart) is currently funded for individuals over 65 years old at the time of the first dose. In the studied cohort in Auckland, the median age at time of onset was 65 years, so patients older and younger than 65 should also consider the vaccine but would currently need to self-fund the treatment. Unlike the previously available live, attenuated vaccine, Shingrix can be given to immunosuppressed patients, who are at higher risk of developing herpes zoster and experiencing recurrent disease or complications.

References

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45(12 Suppl 8):S50-51.

2. Kang JH, Ho JD, Chen YH, Lin HC. Increased risk of stroke after a herpes zoster attack: a population-based follow-up study. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3443-3448.

3. Harding S. Management of ophthalmic zoster. J Med Virol. 1993;Suppl(1):97-101.

4. Niederer R, Meyer J, Liu K, Danesh-Meyer H. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus Clinical Presentation and Risk Factors for Loss of Vision. American journal of ophthalmology. 2021;226:83-89.

5. Aggarwal S, Cavalcanti B, Pavan-Langston D. Treatment of pseudodendrites in herpes zoster ophthalmicus with topical ganciclovir 0.15% gel. Cornea. 2014;33(2):109-113.

6. Gnann J, Jr., Whitley R. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(5):340-346.

7. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster antivirals and pain management. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2 Suppl):S13-20.

8. Meyer J, Liu K, Danesh-Meyer H, Niederer R. Prompt Antiviral Therapy Is Associated With Lower Risk of Cerebrovascular Accident Following Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. American journal of ophthalmology. 2022;242:215-220.

Dr Jay Meyer is an Auckland-based consultant ophthalmologist specialising in cornea/external diseases and glaucoma. He is also a senior lecturer at Auckland University and works in private practice at Eye Institute.

Dr Rachael Niederer is a senior lecturer in the Dept of Ophthalmology, UOA and a consultant ophthalmologist with a special interest in clinical and research aspects of uveitic eye conditions.