Eye to Eye: quizzing the surgeons

Eye Institute’s co-founder Dr Peter Ring and surgeon Dr Kevin Dunne field optometrists’ queries on topics including laser refractive surgery, red-light therapy and the many possible causes of an itchy eye. Answers have been abridged.

Dr Peter Ring Dr Kevin Dunne

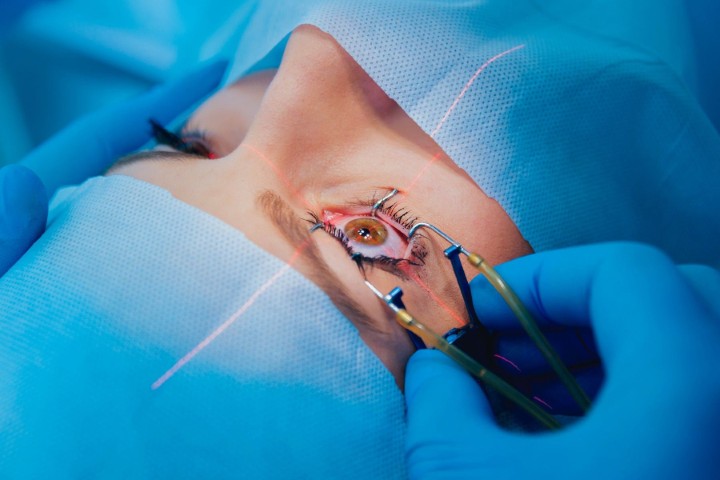

What are the criteria to follow when trying to decide between refractive laser surgery and refractive lens extraction?

Dr Peter Ring (PR)

Laser vision is usually performed on patients between the ages of 20 and 50 and refractive lens exchange is usually for those who are 50-plus. There’s a crossover when presbyopia strikes.

First consider if the patient wants to achieve independence from reading glasses or total independence from glasses. The age of the patient is very important, particularly their presbyopic age. Then consider their refractive error. Looking at hypermetropes first, I’ve never been keen on doing hyperopic laser surgery. In young patients, treat their manifest hyperopia. If you fully treat the latent hyperopia, you're likely to run into postoperative myopic symptoms. And the older hyperopic patient will regress and become more hyperopic with time and the benefit of the laser surgery will be lost within five to six years.

The other problem with hyperopic laser surgery is increasing higher order aberrations, particularly negative spherical aberration and coma, which can create problems postoperatively for the laser patient and more so later on if they become interested in refractive lens exchange. A multifocal lens is not a good idea following hyperopic laser, particularly trifocal lenses, but extended-depth-of-focus lenses might be a bit more forgiving. Older hyperopic patients are ideal for refractive lens exchange because, if they are reasonably hyperopic, you can give them distance and reading vision.

When deciding whether or not to opt for multifocal lenses, I emphasise they are a compromise and it’s not going to give them back the vision they had when they were 35. If they've got good uncorrected acuity of 6/6 and want to get rid of their reading glasses it may make their distance vision worse. So refractive lens exchange in an emmetropic 50-year-old is not without risk.

Patients must be aware they risk ghosting with their reading vision afterwards. That usually settles in two or three months. To avoid halos we mix and match, with a trifocal in the non-dominant eye, which gives good near vision and they’re unlikely to be bothered by halos. In the dominant eye, using an extended depth of focus lens means halos won't be an issue. Reading vision will be further out, but that will help them with computer work.

Intraocular lens (IOL) calculations are more unpredictable following previous laser vision correction surgery. If the patient is in their late 40s, myopic and keen on laser vision correction, warn them they'll lose the ability to read without glasses. Some refractive surgeons overcorrect one eye to give them monovision, which I’m not in favour of, because if you make them minus in their late 40s, they are going to become more hyperopic in their 50s and the effect of the laser will wear off. To counteract that, if you correct to -2D, which will give good reading vision, but you compromise their distance vision. That can be experimented with beforehand using contact lenses.

For some, refractive lens exchanges in myopia, particularly if only 2 to 2.5 diopters, near vision is probably going to be worse than what they could read without glasses. I just wouldn't do it.

High myopes of 4D or above have been quite happy. The other side of the coin for those patients is that there is an increased risk – about 8% – of retinal detachment.

Dr Kevin Dunne (KD)

Have you any thoughts on accommodative IOLs?

PR: Crystalens is the only accommodative IOL we've had so far. It was in a bag and it was meant to move with accommodation. I never thought it was a particularly clever idea or a good principle. There are only about two people in New Zealand who had them and they gave up.

What refractive limits are there with SMILE and what activities are limited following surgery?

PR: The FDA hasn't approved SMILE for treating hyperopia yet and I'm not sure the machines in New Zealand have that capability either.

As in LASIK, the corneal thickness is the refracting limit and it’s a little more limiting than LASIK, because with LASIK we have a 100μm flap at the top, whereas with SMILE there's about 140μm cap before you start lasering out the lenticule. So your range of myopic correction is slightly less limited than with the SMILE procedure.

The FDA has only given approval up to three diopters of astigmatism and some reports suggest that with high myopes there tends to be a bit more regression than one sees with LASIK. If there is myopia afterwards, you have to use either a laser procedure or PRK (photorefractive keratectomy) to correct that error.

In PRK, SMILE and LASIK, the main thing is no swimming underwater for two weeks. With PRK there's a slower visual recovery, so driving, particularly at night, might be delayed for a week or so, whereas with the other two treatments patients are usually driving within one or two days.

Since SMILE has no flap, there's less risk from trauma so it has become the technique of preference for the US armed forces. My advice to LASIK patients for the first week is to avoid squeezing the eyes tightly and avoid eye makeup for a week or two. It's not so much the application of makeup, it's the rubbing off because of the hypothetical risk of moving the flap. They can go back to exercise after a week with any of these treatments but, since sweat in the eyes can lead to rubbing, they should wear a sweat headband.

Is there any new research on red light therapy and supplements to treat or slow down macular degeneration?

KD: There are some early trials looking into red-light therapy, with the key ones being the Lightsite 2 and 3 trials. They are using multiple wavelength light, on the yellow, red and near-infrared spectrum, which is delivered straight to the eye. The initial trial involved 148 eyes in a randomised, sham-controlled clinical trial. The light was delivered for about five minutes per eye in a series of nine sessions over three to five weeks every four months over 24 months.

The idea is the light targets the cytochrome c oxidase enzyme in mitochondria to enhance ATP production, which helps reduce oxidative stress and modulates inflammation in the eye. We're finding evidence that inflammation, even on a microscopic level, has a key role to play in macular degeneration. In mice, they found improved retinal function on electroretinogram following this treatment.

The 24-month data showed the group receiving the light therapy gained approximately five to six EDTRS letters on average, but the sham group also gained about three letters overall. This is quite a small amount of visual acuity improvement, when bigger gains are usually required to say something is a significant for an AMD trial.

One result was only about 6.8% of light-treated eyes developed new geographic atrophy (GA), as opposed to 24% in the sham group, which is a 73% reduction in GA onset.

Possibly they're onto something, but it's hard to say at the moment. They are preparing for a much bigger study with longer study periods and we also want to assess longer-term outcomes.

In terms of AMD supplements, apart from the original AREDS2 (Age-Related Eye Disease Studies), there isn’t much new data on any other supplements that would be recommended for macular degeneration. Inflammation in the eye is an important factor to consider and new complement inhibitor treatments given by injection to target geographic atrophy are in the pipeline.

A patient presents to the optometrist with an itchy, scratchy eye. How do you make sure you’re not overlooking anything indicating a more serious anterior segment pathology?

PR: First, look at the patient to see they don't have an acquired ptosis, for example. You don't want a cataract patient to say after the operation that they developed the ptosis as a result of your surgery! That sounds trivial, but I've seen it before.

Next, look to see if they've got any proptosis or exophthalmos with their eye bulging forward, because that could be a sign of thyroid eye disease. They could have developed exposure keratitis, which you’d see with punctate staining. Ask whether they've had symptoms of hypo- or hyperthyroidism or are being treated for it.

Then check their corrected vision. If it's normal there’s less likelihood of anything serious; if it's not normal, look at the lid margins to see if they've got simple trichiasis with the lashes rolling in and causing the irritation.

There could be trichiasis from the upper lid, which is very uncommon, but you've got to think about scarring of the tarsal plate for a number of reasons, most commonly trachoma. It’s important to look underneath the upper lid because I've seen lymphoma present like that – a fleshy pink lesion. There could be conjunctival melanoma. Or it might be a glaucoma patient with an infected bleb, or even a very large cystic bleb causing irritation.

It could also be a basal cell carcinoma or a squamous cell carcinoma on the lid margin. Basal cell carcinoma is a round pearly lesion with a central core. Ones on the eyelid are much more subtle. One of the signs to look for is a nodule. If the lashes are missing, that’s a hint there might be a basal cell causing the lashes to grow in and irritate the eye.

Another thing to think about would be molluscum contagiosum.

You could find a pseudomembrane on the tarsal conjunctiva, most commonly from adenovirus conjunctivitis. But before you even look there, you might be inferring that from the history, the acuteness of the red eye, the watering and the lack of discharge. In patients with recurrent conjunctivitis, causing itchy, scratchy eye, the thing not to overlook is a blocked tear duct as they might have chronic dacryocystitis.

I recently saw a woman who presented with two lumps in the upper inner part of the orbit, not mobile, but they were firm and a little bit tender. She had blocked ducts and when pressed firmly, a whole lot of pus came out. So check whether the patient's got a long history of a watery eye and see if you can express any pus out of the nasolacrimal duct.

Also consider corneal lesions, such as subtle corneal ulcers like dendritic ulcers, which could be the only clue that the patient has dendritic keratitis. The dendrites are little branching, staining lesions, with bulbous ends. They tend to be more central, as opposed to pseudo-dendrites, which look similar but are a bit more elevated, nearer the limbus and they don't stain as well. They’re a clue that the patient might have had herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO).

Corneal scarring might also present as an itchy eye. Corneal scarring from HZO presents as diffuse little isolated infiltrates scattered over the cornea just below the epithelium, so test for corneal sensation and ask for the history.

You can get corneal changes with recurrent erosions; you might see microcysts, or ‘putty spots’ – little white spots where the epithelium is healing, which may be associated with the history of trauma. Don’t forget map-dot-fingerprint dystrophy and look carefully for those signs in the sub-epithelial tissue.

Other causes of irritation of the cornea which may present with a scratchy eye, but may mean something more serious, are epithelial oedema and associated microcysts. That's uncommon, but one cause is steroid eye drops for a sustained period leading to an acute rise in pressure, sometimes following cataract surgery. The microcysts sometimes coalesce into bullae or cysts and you would see that in a decompensated cornea or Fuch’s endothelial dystrophy.

Lesions on the surface of the conjunctiva, other than pterygia, are a serious thing not to overlook as it could be ocular surface squamous neoplasia. There's conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia and the more serious form of squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. They look quite different from pterygia – gelatinous plaque-like grey lesions usually on the limbus – and can extend as a growth over the surface of the cornea too. In conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia the vessels are like a hairpin, whereas squamous cell carcinomas have a red dot or a strawberry pattern of blood vessels on them.

Is it possible to reduce the risk of vascular issues such as CRAO and BRAO in the eye?

KD: There are ways to improve your risk profile for both branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) and central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO). When I get patients with these, particularly vein occlusions, I tell them it’s an eye problem but it's also a blood vessel health problem – a small stroke in the blood vessel in the eye.

You want to make sure they don't have another major event in the contralateral eye, which could be devastating, so emphasise the importance of a healthy lifestyle, ie. the risk factors are similar to cardiovascular risk factors.

Giant cell arteritis is an inflammatory condition that can cause CRAO, so with any symptoms or any unexplained suggestion of systemic disease, get patients regularly checked by their family doctor for further investigations.

Artery occlusions can also stem from things like arterial emboli, which could come from the carotid arteries, which could be from cardiac valve disease. Atrial fibrillation is also a risk factor for triggering thrombosis and emboli.

I had a patient with BRAO and a little emboli. She had had some chiropractic work around the neck area; that's not the first time I've heard that. So if you team up advancing age with unhealthy blood vessels (atherosclerosis) that can cause a little emboli that goes off to your retina.

With so many anti-VEGFs around, what influences which one you use?

KD: In the private sector, there’s more access to different anti-VEGFs, but in the public system Avastin (bevacizumab) is the main one funded by the government, so it’s one to consider first for neovascular AMD, diabetes or vein occlusions with cystoid macular oedema. Evidence shows it works very well for the large majority of people. Typically you would use a loading dose of one injection every four weeks for a total of three injections, then review.

A secondary treatment is Eylea (aflibercept), which is available on special authority approval. Access to this depends on the underlying disease being treated. In the case of nAMD, to be eligible for Eylea you need to have received three four-weekly injections of Avastin but are still seeing some exudative activity. But with diabetic macular oedema, the criteria are a bit different: you need four injections with no signs of improvement.

Lucentis (ranibizumab) is another common second-line treatment, but it's largely been superseded by Eylea. However, you would still consider using Lucentis if Avastin or Eylea aren't performing well or there are contraindications.

More injections are coming onto the market, including Vabysmo (faricimab), which can potentially give a longer duration of action. However, its real-world data are not quite as good as the trial data show, in terms of duration between injections.

Which OCT hallmarks show a macula has turned from dry AMD to wet?

KD: There are two main hallmarks of wet AMD to look out for: subretinal fluid that's new or signs of intraretinal fluid. But look at this in context; there should be signs to say this activity is coming from macular degeneration. That means seeing retinal pigment epithelium disruptions, drusen or pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) or shallow PEDs. But if you're seeing that in isolation – a little bit of subretinal fluid with a crisp retinal pigment epithelium, or if you're seeing just intraretinal fluid on its own – then it might not be wet AMD.

Sometimes you can see other things that are harder to define, such as subretinal hyper-reflective material or what blood looks like on an OCT.

What’s the place of genetics in medical retina?

KD: That’s a broad topic to answer! We’re in the era of genetics, where the human genome has been mapped and every day we're finding more and more gene variations and the mutations responsible for disease all over the body, including the eyes.

Some inherited retinal diseases come from a single gene defect. The typical signs to cause suspicion are symmetrical findings, a family history and particular patterns on autofluorescence.

You can have electrodiagnostic testing done to find out what a patient has inherited. Auckland’s Greenlane has an ocular genetics service where I refer quite a few patients. They’re really good at compiling investigations and discussing the potential for further genetic testing. They also have information on genetic databases for research and future drug development and offer genetic counselling and family planning. So in terms of the single-gene inherited retinal diseases, such a service adds a lot of value to a patient’s overall care.

The other part of genetics and medical retina would be looking at a host of genetic ‘susceptibility markers’. You can find services online where you send a cheek swab to get your DNA assessed and it'll tell you a risk score for your chances of, say, having macular degeneration. Glaucoma is another big one with identifiable risk factors in your DNA. (For some people with a family history of macular degeneration, they might decide to be tested to show if they are high risk. If they have this information early, they can modify their lifestyle and overall systemic risk factors to try to prevent disease.

In future there will be more of this sort of polygenetic testing and screening and risk scores that can help tailor more targeted treatment for the individual.