Ikigai, allergy, ethics and more!

Guest speaker Malaysian-born, Scottish-trained GP Dr Peter Chai began this year’s Eye Surgery Associates annual optometry dinner with some warm and amusing stories, sharing insights from his career spanning Glasgow and Auckland.

His talk, titled ‘Just GP’, explored the paradox of general practice: often undervalued yet profoundly complex. “We’re the Swiss army knife of medicine,” he said, embracing the broad scope and deep connections unique to general practice. Early in his career Dr Chai held a deep desire to be a radiologist but found himself in Auckland doing paediatrics. “I was quite upset about it, but I’ve moved on,” he said, adding that he thought being a GP was safer than being a radiologist, given the way AI is moving into that space.

Dr Monika Pradhan and Robert Ng

Reflecting on the Covid pandemic, he described how hard it was to be a GP and having to adapt to training under pressure, which reinforced his creativity and care. He learned that, “medicine is more than evidence, it’s poetry, presence and it’s listening”. Ultimately, Dr Chai found his ikigai – his reason for being – in “being an interrogator, healer, guide and teacher,” cherishing daily “lighthouse moments” with patients and colleagues. Reframing the paradox, he said GPs are the foundation of care and education – bringing direction and grounding. His advice to eyecare professionals: “be nice to your GPs, it’s hard work out there.”

To act or not to act?

Also challenging are those conflicting ethical principles faced by eyecare professionals, making it difficult to determine the best course of action, Dr Hussain Patel told those gathered. He grounded his talk on four core principles: respecting a patient’s right to choose, always acting in the patient’s best interests, ensuring fair access to care, and considering confidentiality versus public and private safety.

Presenting cases to illustrate these principles, Dr Patel included one involving a senior patient with severe glaucoma and going blind, who was very resistant to anything but medical treatment. “He declined surgery… he doesn’t listen, but he’s quite comfortable with his choice.” Clinicians must respect informed patient choices, even when the outcome is difficult, he said.

Germain Joblin, Janice Yeoman, Richard Johnson, Ella Ewen

In another case, a patient with vision loss no longer met driving standards but continued to drive. After documenting the risks and informing the patient, Dr Patel realised he faced a confidentiality dilemma. “He ignored everything I said. His daughter was a GP and we agreed we would write to the NZTA.” Breaching confidentiality can be justified where there is significant public risk, said Dr Patel, and this was one of the few acceptable occasions.

Addressing systemic inequities, such as when a migrant patient with advanced glaucoma was unable to access public care or afford private surgery, Dr Patel said clinicians should explore charitable support, emergency-care pathways, or pro bono options, while keeping the patient’s wellbeing central. Professional challenges were also covered, such as managing conflicts with colleagues, dealing with inappropriate financial incentives and balancing care with business demands. Clinicians were urged to reflect, consult colleagues and document their decisions, but always return to ethical fundamentals. The takeaway: ethical care is not just about knowing the rules but applying them compassionately and consistently in practice. “If you are acting in the patient’s best interests, you can’t go wrong,” said Dr Patel.

Cataract and retinal clinic insights

Dr Tracey Wong shared detailed real-world insights from her cataract and retinal clinics, focusing on how pre-existing retinal disease can impact cataract surgery planning and outcomes. Her central message was about careful communication and assessment, treatment and stabilisation, especially for patients with co-existing eye conditions like diabetic retinopathy, AMD, retinal vein occlusion or high myopia.

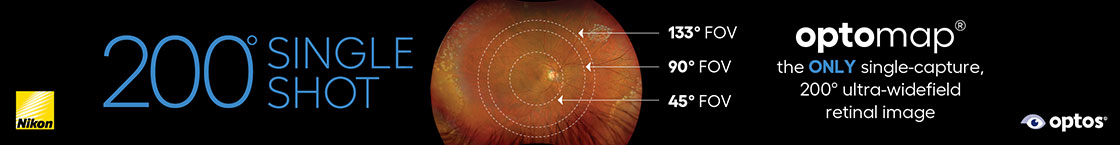

When evaluating patients, she assesses retinal health first, especially in known diabetics or those with macular disease, asking herself, how bad is it, is it stable, has the patient had previous treatment, do they need treatment and, if they have cataract in the mix, in what order should their conditions be treated. Dr Wong cautioned against relying solely on widefield camera photos – black and white photos will show things up much more clearly, while autofluorescence, infrared, pre- and post-op OCT imaging and sometimes B-scan ultrasound are needed to fully understand macular or peripheral disease.

Dr Ye Wei Goh and Gary Filer

Set out expectations clearly to patients, especially in high myopes or those with advanced macular damage who may not get full visual recovery, she said. For example, post-op floaters are common and usually benign but are sometimes more obvious after surgery and should be discussed with patients ahead of time. Dr Wong also recommended writing clear referral notes to guide treatment and avoid surprises.

Why those scratchy eyes?

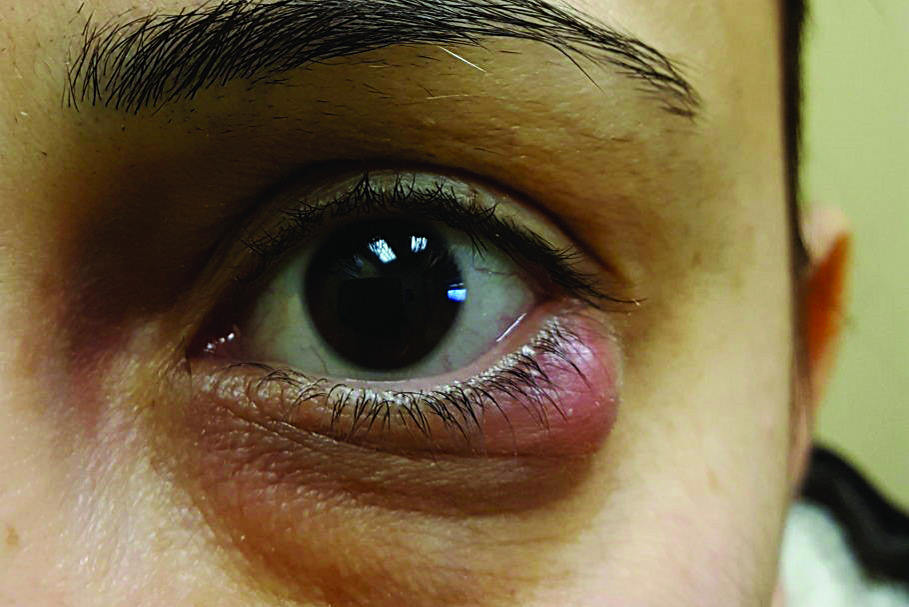

Dr Yi Wei Goh shed light on the world of allergic eye disease (AED), a chronic, relapsing spectrum of conditions which carries significant risks for vision if overlooked. Conditions range from mild seasonal allergies to severe chronic inflammatory disease. Mast cells, eosinophils and cytokines play a key role, causing itching, redness and swelling and chronic inflammation. AED’s global prevalence is about 20 to 40% (up to 25% in Maori and Pasifika) with a higher incidence in warmer climates, said Dr Goh. The five main types are:

- Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC), triggered by pollen

- Perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC), caused by indoor allergens

- Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), severe and seasonal

- Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), chronic and associated with atopic dermatitis, asthma and hay fever, heightened risk of keratoconus and even retinal detachment

- Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC), contact lens related.

The most common types are SAC and PAC, with itching, redness, watery discharge and swollen eyelids, while GPC is a reaction to lid movement over a foreign substance, said Dr Goh. Clinically, VKC can be striking, she noted. “Think cobblestone papillae over a millimetre on the upper tarsal conjunctiva, thick ropy mucus and shield ulcers on the cornea.” AKC is a chronic, bilateral disease with eyelid eczema and a notorious tendency for corneal scarring and neovascularisation, she said.

Khyati Jindal, Rahul Parmar and Nathan Sapsford

Complications of AED include: keratoconus as a result of eye rubbing, glaucoma and cataracts from long-term steroid use risks, and dry eye disease from ocular surface disruption. Patients with active atopic disease fare poorly after ocular surgery and face an elevated risk of retinal detachment. It is vital to differentiate inflammatory changes from neoplastic lesions like limbal masses, said Dr Goh, and to use topography to pick up subtle keratoconus or irregular astigmatism.

Careful stepwise management for mild to severe cases starts with education, allergen avoidance, cold compresses and lubricants, escalating to topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilisers, and then cautious steroid use. For advanced treatment, Dr Goh advocated for immunomodulators such as cyclosporin or tacrolimus, and even systemic immunosuppression for AKC and referral to immunology or dermatology.

David Choi, Cherie Lou, Lucy Na, Lilian Zhang, Joyce Wong and Lisa Lu

“Patients often present late, with vision-threatening disease,” she said. “Relapses are common, and adherence is tough, especially in children who rely on parents.” Ultimately, she underscored that allergic eye disease isn’t a minor nuisance: “It’s hard managing these patients and the complication risk is much higher.” Early recognition, multidisciplinary coordination and relentless follow-up remain the best safeguards for sight, she said.

Systemic medicines?

Dr Monika Pradhan presented a comprehensive review of retinal and optic nerve complications associated with systemic medications, emphasising the importance of taking a detailed history for all eye patients – even those presenting with seemingly routine issues.

She illustrated the issue with a case concerning a woman on chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel) who developed retinal vascular occlusions: “big cotton wool spots”. Her symptoms – acute superior visual field defect and subtle retinal change – could easily have been misattributed to her diabetes. However, Dr Pradhan recognised the significance of her oncology treatment. Chemotherapy agents can cause vascular damage, including ischaemic optic neuropathy and retinal occlusions, due to their pro-thrombotic effects. Prompt communication with the patient’s oncologist led to cessation of the final chemotherapy cycle and stabilisation of vision.

Dr Pradhan stressed that patients often do not disclose treatments unless asked directly, citing the case of a macular degeneration patient who only revealed his stem cell transplant at the end of the consultation. She categorised drug-induced retinal effects into mechanisms ie. retinal pigment epithelium disruption (eg. hydroxychloroquine), vascular damage (eg. chemotherapy, contraceptives), uveitis-like reactions (eg. checkpoint inhibitors), cystoid macular oedema (eg. fingolimod) and crystalline retinopathies (eg. tamoxifen).

Specific screening protocols, especially for hydroxychloroquine, were discussed, including the importance of SD-OCT and visual field testing adapted for ethnicity. Dr Pradhan’s key message: stay alert to systemic medications, particularly newer immunomodulatory and oncology agents, which may present subtly but can lead to irreversible vision loss if overlooked.

Bookending the evening, Dr Chai provided an illuminating example reinforcing Dr Pradhan’s key message by asking the room about the possible cause of one 47-year-old woman’s visual disturbances. She had signs of retinal vein occlusion (RVO), including inferior retinal haemorrhages and vessel dilation, but no prior history of hypertension or diabetes. One quick audience member correctly guessed the patient was menopausal. This was confirmed after Dr Chai said her symptoms had appeared after starting oestrogen-based hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to manage severe menopause symptoms.

Dr Peter Chai awards waiter Luke Trujilllo his prize

This case also raised awareness of a possible, but rare, link between oestrogen therapy and ocular vascular events. Dr Chai advised clinicians to monitor visual symptoms closely in patients starting HRT, discuss risks and benefits thoroughly and refer promptly if new visual changes occurred. The case also highlighted the importance of writing detailed referral letters, he said, as well as the importance of shared decision-making and timely collaboration between GPs, optometrists and ophthalmologists.

The evening ended on a high note with the venue’s attentive waiter, Luke Trujillo, correctly answering Dr Chai’s question: what percentage of GPs will retire within the next 10 years? (answer: 54%), winning himself a book: Biopsies by New Zealand author Greg Judkins for his efforts.