Radio host recalls how an optometrist saved her life

At 21, Dani Fennessy was 10 minutes away from having coffee with a friend. She never made it! Instead, a routine eye check by a Specsavers optometrist forced her to re-route immediately to the hospital. That appointment and the optometrist, who saw what she couldn’t, “saved my sight – and my life,” she said.

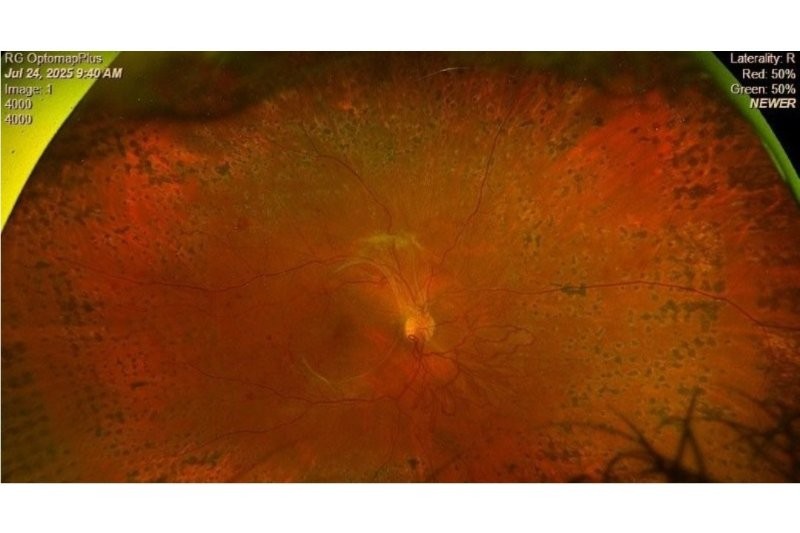

The optometrist found Fennessy had swelling on her optic nerve – an “invisible, insidious threat” that would change her life. Fennessy was diagnosed with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), increased pressure on the brain with no known cause. “Little did I know it was to become a part of my life forever,” Fennessy told a rapt RANZCO NZ 2025 audience in Rotorua as the only non-medical keynote.

After having tests, she required an emergency lumbar puncture to relieve the pressure and an MRI to rule out a brain tumour. At this point, she met eye specialist Professor Helen Danesh-Meyer, who she described as, “My hero who has inspired me for 10 years.”

Now a 34-year-old media personality and patient advocate, Fennessy says her journey from diagnosis was immediate and brutal – medication, invasive testing, fear. “Long story short, I was put on medication, stabilised and got on with life,” she said.

Fired by ambition Fennessy chased her dream to work in radio. She got there – her own show, her voice on air, everything she had worked for. She silenced the whispers of fatigue, headaches, ringing ears and blurred vision over a number of years and, in the rush of deadlines, meals eaten in her car and “caffeine-fuelled ambition”, she ignored it all. Then Covid hit. She lost her job, her identity crumbled and her health finally demanded her attention. “Stress was literally killing me – and that’s when it happened,” she told the packed conference chamber. Her vision distorted, “like looking underwater”; blurry in one eye, there was nothing in her left eye and she was rushed to hospital. “My stubbornness was replaced by paralysing fear,” she recalled. The lumbar puncture took 12 painful attempts and when her mum’s composure cracked, Fennessy knew it was serious.

The months that followed were dark, said Fennessy. Water tasted like metal, medicines clouded her brain and threatened her dream of motherhood. IIH is a diagnosis linked to obesity, which layered on guilt and shame, given her weight. “Mental breakdowns in the bathroom,” she recalled. Because the pressure in her eye was so high, it pressed on her optic nerve, causing permanent damage. She now has a blind spot in her left eye, she said. “Prof Danesh-Meyer dubbed me ‘the unicorn’”, as losing sight permanently with IIH is very rare.

From that moment on, “everything changed – how I lived, ate, existed,” said Fennessy. Losing her vision helped her to see. She started taking care of herself, she lost weight, she goes to Greenlane eye clinic for check-ups every three months. “I wasn’t just fighting for my health but for my future.”

Step by step, scan by scan, Fennessy clawed her way back. From 16 pills a day to none. Seven months ago, she was stable enough to stop medication and try for a baby.

Fennessy now runs an IIH website, to help others with the condition and promote education and research, plus a healthy woman platform, both with support and help from some of the ophthalmologists she’s met on her journey.

Her message to eyecare professionals: “Don’t ever underestimate the power of what you do; you’re not just a practitioner you are the reason your patients get to dream.”