Māori perspectives of ocular healthcare: addressing inequitable health outcomes in ophthalmology

Tēnā tātou katoa,

Tēnei rā te mihi whakatau ki nga manuhiri, ko wai ta mātou e tono ki te whakapuaki, I ta mātou tirohanga me te tautoko, mo te iwi Māori o Aotearoa, me te hauora kanohi

This is a welcome to our audience, whom we invite to share our vision and support

for Māori people of Aotearoa and eye health. Kia ora

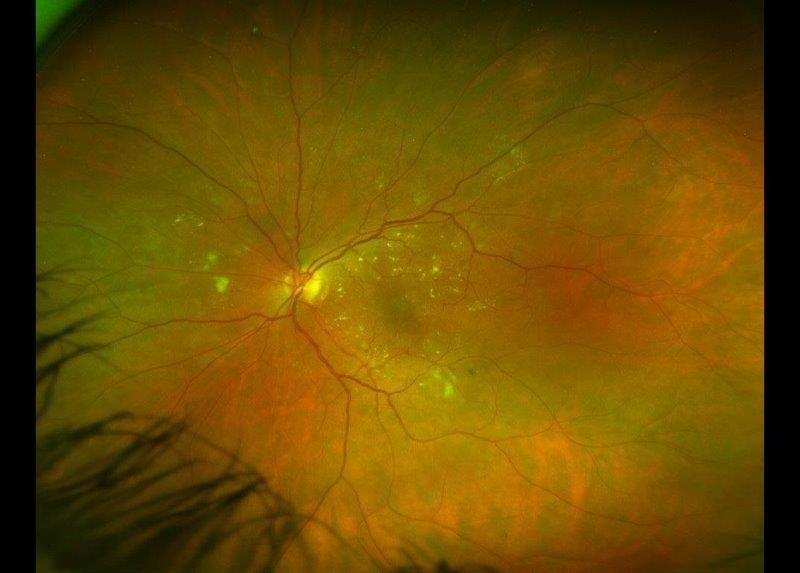

Ophthalmology is one of the most rapidly advancing fields of medicine, with new technologies, diagnostic modalities and treatments emerging almost daily. While advances in medicine and technology are essential to the provision of high-quality healthcare, issues surrounding equity and access to services persist1,‑2. Within Aotearoa New Zealand, these issues disproportionately affect the Indigenous population of Māori, in relation to both ocular and general health outcomes. Māori have a higher prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and keratoconus, develop cataracts 10 years younger than non-Māori and have decreased access to strabismus surgery compared to non-Māori3-5. This evidence indicates inequities within our ocular healthcare system, which is failing to adequately serve Māori.

Growing efforts to address Indigenous inequity are becoming apparent within the realm of ocular healthcare, most recently within Australia with its focus on Indigenous people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders9. Indigenous engagement models in Aotearoa, such as Te Whare Tapa Whā (The House With Four Walls) and the Meihana model, may provide valuable insights to eyecare clinicians to begin addressing these issues and acknowledging the importance of enhancing the relationships between all clinicians and Māori patients7-8.

Qualitative research allows light to be shed on the Māori healthcare experience within Aotearoa9. What these projects lack in statistical strength is more than compensated for in the heard voices of those who have suffered, indicating a need for change from a first-hand perspective. This aligns with kaupapa Māori methodology, in which sovereignty and Māori voices are to be protected and valued10.

This article presents, with the editor’s permission, a summary of a 2021/22 Ocular Surface Laboratory (OSL) summer student research project, the outcomes of which are described in full in an invited submission, accepted for publication in an Indigenous Eye Health special issue of Clinical and Experimental Optometry in 202311. It seeks to introduce the benefits of qualitative kaupapa Māori research in identifying and understanding Indigenous health inequities within the ocular health sector in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Methods

The study recruited adult participants who identified as having Māori ethnicity and ancestry or whakapapa (genealogical links to historical Māori individuals). Recruitment was conducted by the research team’s Māori students and guided by kaupapa Māori methodology, using established professional and personal networks.

The study population included 15 eligible and consenting Māori community members who participated in one of three online focus groups (via Zoom), as well as three Māori eyecare practitioners who participated in individual interviews conducted by the project’s lead Māori researcher. Focus groups and interviews were semi-structured and began with a short video developed by the research team, which depicted standard (Western) ocular examination techniques to provide context to the discussion. Focus group discussion topics ranged from the integration of Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview) and vision to access and barriers for accessing ocular healthcare in Aotearoa. Audio recordings of focus groups and interviews were transcribed and analysed using NVivo qualitative analysis software. Thematic analysis was undertaken once inductive coding and experiential orientation to codes had been performed by two researchers. This ensured the essence of participants’ thoughts and considerations was accurately captured and themes highlighted were of value to the researchers, participants and potential readers of research outputs12.

Results

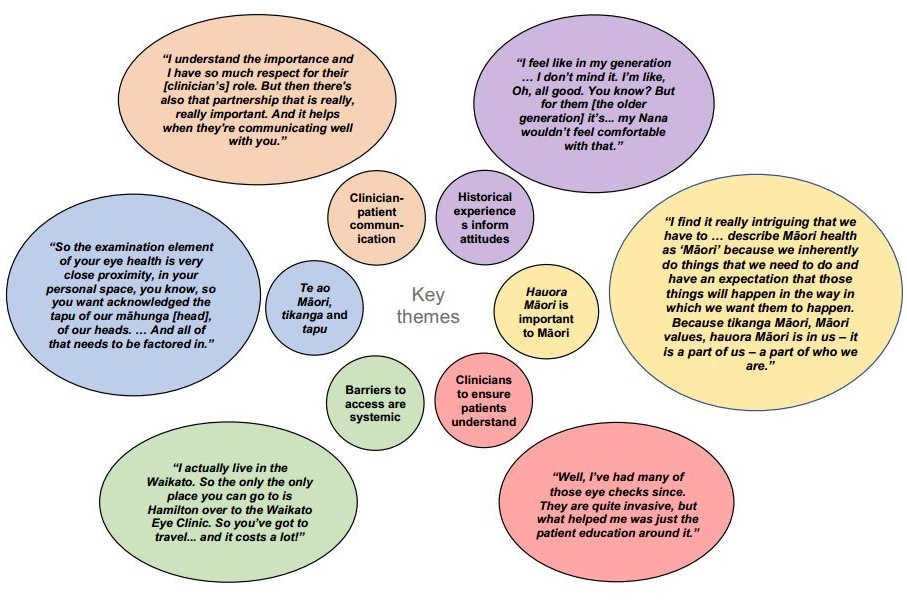

Fig 1 provides a summary of the six core themes identified from the data analysed, together with a representative quote, with five of these having been described previously11, these being:

Clinician-patient communication

All participants highlighted the importance of adequate and effective communication between the clinician and the patient. This includes appropriate and genuine introductions and whakawhanaungatanga (the building of connections) before the initiation of the clinical component of the consultation. Participants also highlighted the need for this to be clinician-led due to the perceived power imbalance between patients and clinicians.

Patients’ historical experiences inform their health attitudes

Participants discussed the influence of personal experiences on their health attitudes. These ranged from the impact of colonisation and early Western medical research on Māori to whānau (family) experiences of receiving ocular healthcare. Positive experiences correlated with a high likelihood of participants being willing to return to services, while negative experiences served as deterrents.

Barriers to access are systemic

During discussion of access to services, participants referred to the systemic nature of barriers to accessing services. This included geographical location, particularly rurality, as well as the lack of services in more remote areas, lack of finances and transport.

Hauora Māori (Māori health) is important to Māori

When asked about hauora Māori, all participants discussed the holistic nature of wellbeing and health within the Māori worldview. This includes the importance of spiritual, mental, family and physical health, all contributing to the wellbeing of an individual. This concept was deemed essential to Māori, and participants highlighted their desire for this to be recognised during medical consultations.

Te ao Māori, tikanga and tapu

The concepts of te ao Māori, tikanga (customs/traditional practices) and tapu (sacredness or restriction) are important to Māori and their health. Participants discussed tapu, stating that due to the sacredness of a Māori individual’s head, it is important to seek consent and explain the necessity of a procedure or investigation before a clinician touches a patient’s head. However, most participants stated that in acute settings, ensuring preservation of physical wellbeing and vision would override this requirement.

Subsequent analysis teased out a sixth sub-theme, which highlights a responsibility for eyecare professionals to provide clear explanations, to educate patients and their whānau on matters relevant to their diagnosis and treatment plan.

The clinician’s role in ensuring patient understanding

The impact a clinician can have, as an educator of patients and their family, cannot be overstated, with the potential to enhance both the physical health and health literacy of the patient. Participants in the study described the importance of being adequately informed and educated by their ophthalmologist during clinical consultations and the effect it had on their healthcare experience.

“Well, I’ve had many of those eye checks… they are quite invasive,

but what helped me was just the patient education around it.”

The quote above indicates that despite participants having reservations about the invasiveness of procedures, they are more likely to have a positive experience if the explanations surrounding the examination have been adequate.

Participants also described fear arising from lack of knowledge when attending an ophthalmology clinic and the impact education may have on enhancing their health literacy.

“Health literacy is a big one (barrier). My cousins, all my aunties and uncles, when they go to the doctors and they just say all these big words, they get scared.”

“Equity. To be treated as equal and everyone treated the same and to be informative with the information… You’ve got to be able to show versatility in being able to cater to the patient, to the learning capability.”

These quotes indicate both the need and desire for clinicians to provide adequate explanation and to ensure patient understanding is prioritised during clinical consultations.

Discussion

All six themes allude to factors that call for enhanced cultural safety within ocular healthcare. Cultural safety differs from cultural competency by shifting the focus from simply learning about language or traditions and taking a more introspective approach by reflecting on one’s own cultural journey and how this influences personal biases or interactions with others13. Culturally safe practice seeks to bridge the gap between clinician and patient by eradicating power imbalances and ensuring high quality communication is prioritised.

Māori engagement models have become commonplace in medical education throughout Aotearoa with the Hui process and Meihana model (two clinical engagement models from the University of Otago) now being integrated into medical school curricula7-8,14. These frameworks enhance the acknowledgement of hauora Māori within a clinical context to improve relationships between Māori patients and clinicians14. The inclusion of such models within ophthalmology training programmes and professional accreditation courses may see a shift towards a more culturally safe workforce and enhance relationships between Māori patients and ocular healthcare clinicians in Aotearoa.

Development of frameworks, accreditation curricula and policy which focus on culturally safe clinical practice are ongoing. By enhancing patient experiences within ocular health services, we have an opportunity to contribute to healing the relationship between the Indigenous population of Aotearoa and the New Zealand health system, to enhance the vision of Māori and begin addressing ethnic ocular health inequities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of our co-authors Associate Professor Donna Cormack, Dr Alex Müntz, Dr Sarah-Jane Paine and the supervisor for this research project, Professor Jennifer Craig.

References

- Whānau Ora. Inquiry in Māori health inequities. Auckland: Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency 2019 (pp. 1-10, Rep.)

- Reid P, Robson B. Understanding health inequities. In: Robson B, Harris R, eds. Hauora: Màori Standards of Health IV. A study of the years 2000–2005. Wellington: Te Ròpù Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pòmare, 2005. p 3-10

- Chong C, Lawrence A, Allbon D. Addressing equity: a 10-year review of strabismus surgery in 0-19-year-olds in the New Zealand public health system. N. Z. Med J. 2021;134: 79-90

- Chilibeck C, Mathan J, Ng S, et al. Cataract surgery in New Zealand: access to surgery, surgical intervention rates and visual acuity. N. Z. Med. J. 2020; 133: 40-49

- Wilkinson B, McKelvie J. Evaluating barriers to access for cataract surgery in Waikato: analysis of calculated driving distance and visual acuity. N. Z. Med. J. 2021; 134: 105-112

- Bentley S, Anstice N, Armitage J, et al. Strengthening Indigenous eye care in Australia and New Zealand through a Leaders in Indigenous Optometry Education Network. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2021; 45: 89-92

- Rochford, T. Whare Tapa Wha: a Māori model of a unified theory of health. J Prim Prev 2004; 25: 41–57

- Pitama S, Huria T, Lacey C. Improving Māori health through clinical assessment: Waikare o te Waka o Meihana. N. Z. Med. J. 2014; 127: 107–119

- Walker R, Walker S, Morton R, et al. Māori patients' experiences and perspectives of chronic kidney disease: a New Zealand qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2017; 7: e013829. Published 2017 Jan 19. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013829

- Smith L, Decolonizing methodologies, 2nd ed. London, UK: Zed Books, 2012

- Samuels I, Cormack D, Pirere J, et al. Ngā whakaaro hauora Māori o te karu: Māori thoughts and considerations surrounding eye health. Clin Exp Optom 2022 (online ahead of print).

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006; 3: 77-101

- Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019; 8: 174

- Wilson D, Moloney E, Parr J, et al. Creating an Indigenous Māori-centred model of relational health: a literature review of Māori models of health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021; 30: 3539-3555.

Isaac Samuels (Tainui, Ngāti Hauā, Ngāti Tuwharetoa) is a BMedSci (Hons) student, working in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Auckland, and lead Māori researcher on the project discussed in this article. He will become a trainee intern at Middlemore hospital in 2023, where he hopes to continue his clinical and research journey to better serve his Māori communities.

Julie Pirere (Ngaati Awa, Te Arawa), a bachelor of Māori Registered Nursing student with Manukau Institute of Technology, completed a summer studentship with the OSL team at the University of Auckland and is passionate about continuing to serve Māori communities in the future.