Azithromycin as an MGD treatment

The common use of oral antibiotics in the management of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is an extension of the traditional dermatological approach to rosacea treatment. In this context, historically, oral tetracyclines have been used for their anti-inflammatory properties (anti-matrix metalloproteinases, bacterial lipase inhibition and fatty acids reduction), rather than antibiotic properties per se1,2. To achieve this effect, oral tetracyclines require three- to four-month courses, which increases the likelihood of compliance-limiting side effects, such as skin photosensitivity and gastro-intestinal upset. Tetracyclines are also contraindicated in children due to deposition in growing bone and teeth. In contrast, oral azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic which acts as an immune-modulator, only requires a short (often three-day) weight-related course and has no age-related contraindications2,3. Its additional treatment advantages include potent anti-inflammatory activity, anti-bacterial effects with a high efficacy spectrum, daily dose pharmacokinetics and favourable eyelid tissue penetration1-4.

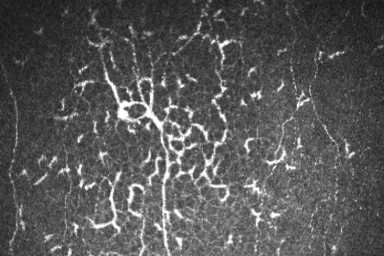

Small clinical studies have compared the use of oral azithromycin with oral doxycycline for MGD and while they acknowledged clinical improvement in both treatment groups, they recommended oral azithromycin due to better overall improvement in conjunctival redness and ocular surface staining5,6. Azithromycin has been shown to improve cellular function by directly increasing lipid accumulation and promoting terminal differentiation of human meibomian gland epithelial cells in vitro (unlike tetracyclines)7. There are obviously compliance benefits with this approach (three days versus three months), which has also been demonstrated to be nearly three times less expensive2. A recent systemic review reported MGD could be treated effectively with either oral or topical azithromycin, improving symptoms, clinical signs and stabilisation of tear film. Greater short-term improvements in the tear film quality was even reported with topical azithromycin compared to orals8. In fact, an increasing number of publications show benefits from the now-available topical azithromycin preparations[1] in the treatment of MGD, presumed due to the high local tissue drug concentrations, with clinical improvements reported to persist beyond one month following treatment9.

However, oral azithromycin is not the perfect drug. A US Food and Drug Administration drug safety communication alert in 2013 raised concern about the risk of potentially fatal heart rhythms due to QT interval prolongation with Zithromax (oral azithromycin). They advised caution in patients who are already at risk for cardiovascular events, yet also noted that alternative drugs in the macrolide class, and non-macrolides such as the fluoroquinolones, also have the potential for QT prolongation. It should also be acknowledged that there is a lack of high-level evidence supporting the use of oral azithromycin in MGD. A Cochrane review in 2021 only identified two papers of randomised controlled trial quality, which meant they could not find sufficient evidence to draw any meaningful conclusions for any of the oral antibiotics currently advocated for use in chronic blepharitis10.

In light of these issues, the wise clinician should remain cautious in their prescribing of any systemic medication and mindful of the pros and cons of these management strategies, with decisions made on an individual patient basis. While no treatment is not without some risk, the literature is clear that oral azithromycin is better tolerated and more effective in the majority of patients than oral tetracyclines. In my practice, in adults, that is often 500mg azithromycin for three days, repeated in three to four months (alongside the usual lid heat and hygiene with anti-Demodex action measures and regular ocular lubricants). In the future it may be that topical azithromycin will offer a relatively safer option as early evidence shows good effectiveness in treating patients with MGD.

*Topical azithromycin is not an approved medicine in New Zealand at the time of publication.

References

1. Qiao J, Yan X. Emerging treatment options for meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol 2013; 7: 1797– 803.

2. Al-Hity A, Lockington D. Oral azithromycin as the systemic treatment of choice in the treatment of meibomian gland disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Apr;44(3):199-201.

3. Choi D, Djalilian A. Oral azithromycin combined with topical anti-inflammatory agents in the treatment of blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. J AAPOS 2013; 17: 112– 3.

4. Greene J, Jeng B, Fintelmann R, Margolis T. Oral azithromycin for the treatment of meibomitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan;132(1):121-2. PMID: 24201556.

5. Kashkouli M, Fazel A, Kiavash V, Nojomi M, Ghiasian L. Oral azithromycin versus doxycycline in meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomised double-masked open-label clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 99: 199–204.

6. Igami T, Holzchuh R, Osaki T, Santo R, Kara-Jose N, Hida R. Oral azithromycin for treatment of posterior blepharitis. Cornea 2011; 30: 1145– 9.

7. Liu Y, Kam W, Ding J, Sullivan D. Can tetracycline antibiotics duplicate the ability of azithromycin to stimulate human meibomian gland epithelial cell differentiation? Cornea 2015; 34: 342–6.

8. Tao T, Tao L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of treating meibomian gland dysfunction with azithromycin. Eye (Lond). 2020 Oct;34(10):1797-1808.

9. Yildiz E, Yenerel N, Turan-Yardimci A, Erkan M, Gunes P. Comparison of the Clinical Efficacy of Topical and Systemic Azithromycin Treatment for Posterior Blepharitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2018 May;34(4):365-372.

10. Onghanseng N, Ng S, Halim M, Nguyen Q. Oral antibiotics for chronic blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jun 9;6(6):CD013697.

Dr David Lockington is an active educator, speaker and cataract and corneal ophthalmic surgeon based in Glasgow, UK. He underwent sub-specialty fellowship training in cornea and anterior segment at the University of Auckland, where he remains an honorary clinical senior lecturer.