Treating computer vision syndrome – what does the evidence say?

Computer use is ubiquitous in contemporary society. Up to 69% of computer users report eye strain1,2, sometimes referred to as ‘computer vision syndrome’ (CVS) or ‘digital eye strain’. Although a range of interventions have been investigated for this common condition, currently there are no clinical guidelines to help practitioners provide evidence-based advice about CVS treatments.

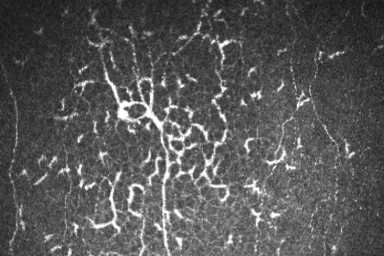

Researchers from the University of Melbourne and Centre for Eye Research Australia, conducted a systematic review to identify, appraise and synthesise clinical evidence relating to the efficacy and safety of interventions for treating computer vision3. Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this review and the pre-specified primary outcome measures evaluated were visual fatigue symptoms and critical flicker-fusion frequency (as an objective indicator of eye fatigue). Secondary outcomes focused on quality of life, dry eye symptoms, amplitude of accommodation, near point of convergence, blink rate and overall patient satisfaction with the intervention.

This comprehensive review included 45 clinical trials that were published between 1991 and 2021. These studies investigated a diverse range of potential treatments, including optical aids, oral complementary and nutritional supplements, artificial tear products, environmental modifications, ergonomic adjustments, yoga and visual hygiene procedures (such as the 20/20/20 rule). The studies were conducted across 11 countries (Japan, India, United States of America, Hong Kong, Korea, China, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Norway, Spain and the UK) and collectively involved 4,497 participants.

The review found multifocal lenses did not improve visual fatigue scores compared to single-vision lenses in young adult computer users, according to very low certainty evidence. Likewise, oral berry extract supplements, which are purported to have antioxidant properties, were found not to be beneficial relative to placebo supplements, in reducing visual fatigue or dry eye symptoms associated with computer use. Another intervention category, which has also received attention for its potential role in reducing ocular surface inflammation as a dry eye management strategy, was oral omega-3 fatty acid supplementation4. In the context of computer vision syndrome, it was found with low certainty that treatment with oral long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for 45 days to three months had a clinically significant benefit in reducing dry eye symptom scores relative to placebo. However, this finding was based on data from only two studies conducted by the same research group. There was also greater participant dropout, due to gastric intolerance, among individuals assigned to a higher dose of omega-3 fatty acids (n=26, 1440mg eicosapentaenoic acid + 960mg = docosahexaenoic acid per day) compared to a lower dose (n=6, 720mg eicosapentaenoic acid + 480mg docosahexaenoic acid per day). Further research is required to more clearly define whether omega-3 fatty acid supplements are useful in the management of computer vision syndrome.

Blue-light filtering lenses, which are frequently prescribed in eyecare practice5, were found to be ineffective in reducing symptoms of visual fatigue compared to non-blue light-filtering lenses, according to the findings from three studies. Although recommendations for artificial tears are common for the management of dry eye disease, based on findings reported from a single study, this review found very low certainty evidence for the role of artificial tears in reducing symptoms associated with computer use compared to no intervention. A further intervention that was evaluated was the 20-20-20 rule, a common recommendation in practice where patients are advised to view an object 20 feet away for a total of 20 seconds every 20 minutes, with the intention of relaxing accommodation and convergence. Only one study that evaluated the 20-20-20 rule was found and provided very low certainty evidence for reducing dry eye symptoms compared to a placebo intervention comprising the intake of water.

Overall, this systematic review found a lack of high certainty evidence for any therapies currently used in practice to manage computer vision syndrome. High-quality clinical trials are required to clarify the efficacy and safety of therapies for this condition. The review also highlighted a range of limitations in the design, conduct and reporting of many previous RCTs, and provided recommendations for how these shortcomings might be addressed when designing future CVS clinical trials.

The full research was recently published in Ophthalmology, www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(22)00361-X/fulltext

References

- Ranasinghe P, Wathurapatha WS, Perera YS, et al. Computer vision syndrome among computer office workers in a developing country: an evaluation of prevalence and risk factors. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:150

- Blehm C, Vishnu S, Khattak A, et al. Computer vision syndrome: a review. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50(3):253-62

- Singh S, McGuinness MB, Anderson AJ, Downie LE. Interventions for the management of computer vision syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2022 May 18 (online ahead of print).

- Downie LE, Ng SM, Lindsley KB, Akpek EK. Omega‐3 and omega‐6 polyunsaturated fatty acids for dry eye disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12):CD011016.

- Singh S, Anderson AJ, Downie LE. Insights into Australian optometrists’ knowledge and attitude towards prescribing blue light‐blocking ophthalmic devices. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 2019 May;39(3):194-204

Dr Sumeer Singh is a postdoctoral clinical research fellow at the Downie Laboratory: Anterior Eye, Clinical Trials and Research Translation Unit, in the Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences at the University of Melbourne.